Greene Naftali

Exhibition

Tony Cokes

On Non-Visibility

8th Floor

Press Release

Download PDF

Since the early 1980s Tony Cokes has developed a precise visual and discursive style marked by videos that feature animated text, found images, solid-color slides, and pop music. In his work Cokes samples and subverts modes of representation and cultural fragments from the media—in particular news, advertising, and Hollywood cinema—reframing the images and ideas that are designed to construct our habits and identities. By extracting source texts from their original contexts and layering elements that often clash, Cokes analyzes media’s operations and the ways in which they manifest power. On Non-Visibility, Cokes’s first gallery exhibition, presents a historical cross section of his practice, focusing in particular on the titular theme.

The earliest piece in the exhibition, Black Celebration (1988), is projected in the gallery’s center room. In the video Cokes pairs footage from the 1965 riots in Watts, Boston, Detroit, and Newark with text by The Situationist International, Barbara Kruger, Morrissey, and Depeche Mode’s Martin L. Gore, along with music by the industrial band Skinny Puppy. The piece “[introduces] a reading that will contradict received ideas which characterize these riots as criminal or irrational," Cokes has said. The postmodern techniques and sources employed in Black Celebration had been present in Cokes’s early audio-visual work—which throughout the ’80s was shown in venues such as The Kitchen, Artists Space, the New Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art—and have filtered and mutated through his oeuvre in the ensuing thirty years, for example with his four-person “art band” X-PRZ (1991–2000) and in series of work like Pop Manifestos (1999–2004) and Evil (2003–ongoing).

The Evil series features prominently in On Non-Visibility. Investigating the way culture is created and framed in post-9/11 America, in an information landscape defined increasingly by internet usage and consumption, the Evil videos often feature monochromatic, text-laden slides set to music, distilling—even abstracting—the heterogeneous information that Cokes samples to expose popular rhetorics of power. The texts in the Evil series quote government testimonies, speeches, pop lyrics, stand-up comedy, and other sources; with the texts presented in motion, and bright colors and music behind them, the videos demonstrate how media flattens discourse and scrambles meaning production.

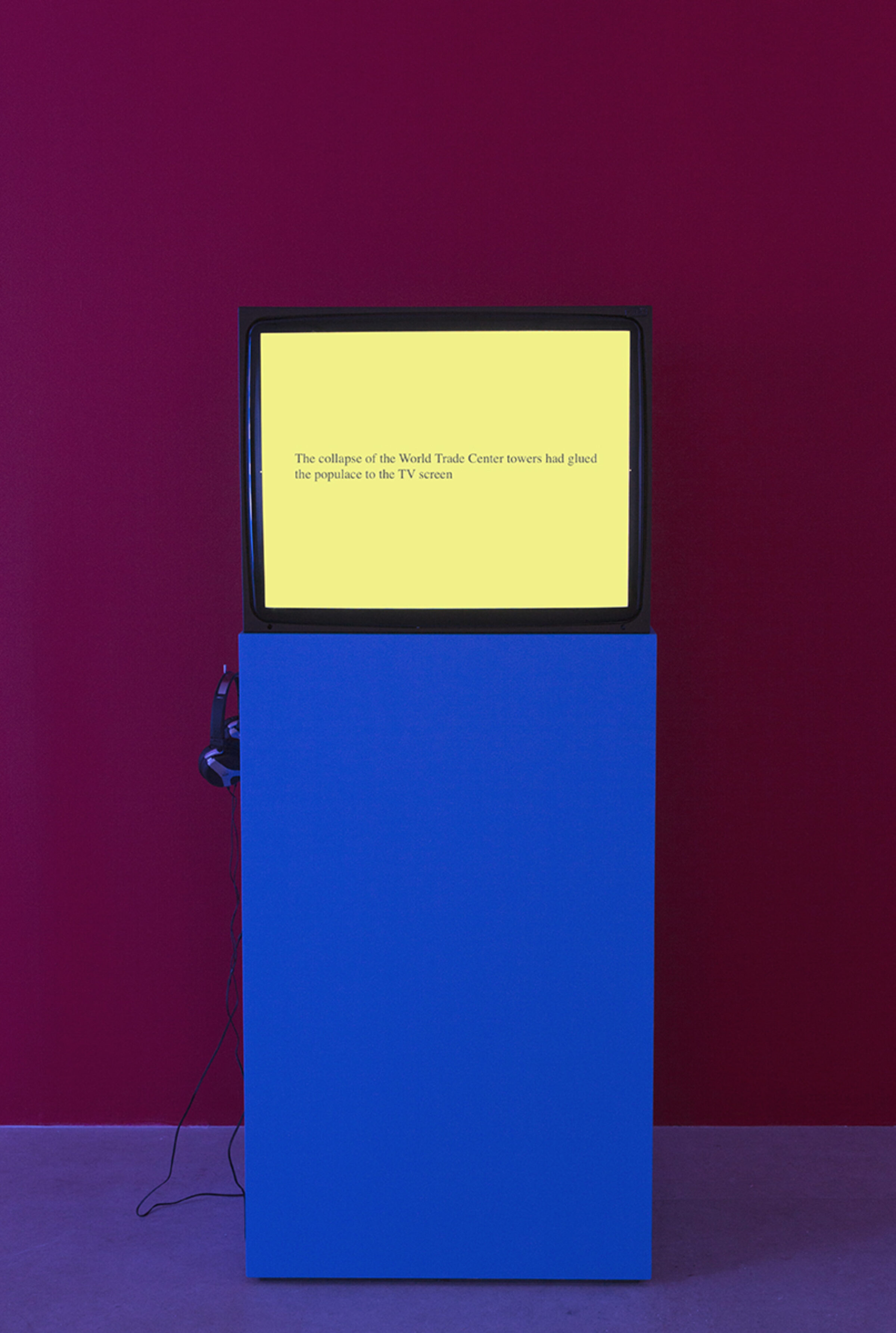

The combination of text slides and found footage in Black September (Evil.2/3) (2003), which uses footage by Michelangelo Antonioni, text from terrorism.com, and music by experimental pop group The Notwist, positions it as a bridge between Cokes’s early and more recent work. In On Non-Visibility the piece plays on a cube monitor, as does Evil.12.edit.b (fear, spectra & fake emotion) (2009), which employs text by social theorist Brian Massumi and music by the electronic artists Modeselektor and Deadbeat.

Two large LED panels display three more videos: one panel shows Evil.35: Carlin/Owners (2012), which uses text from comedian George Carlin set to music by the post-punk band Gang of Four, while the other panel alternates between Evil.66.1 (2016), which uses text from Donald Trump with music by Pet Shop Boys, and Evil.16: Torture Musik (2011), which deploys an article from The Nation on the subject of the use of pop music in “enhanced interrogation techniques,” set to a variety of familiar songs. Each of these videos employs the red-and-blue color scheme that characterizes recent works by Cokes including Face Value, a 2015 video whose slides—here, quoting Lars von Trier and Kanye West—are printed on two lightboxes in On Non-Visibility.

Mimicking 21st-century modes of cultural production and consumption, the Evil works highlight how those in power render certain events visible or non-visible, and certain voices loud or silent. Evil.27: Selma (2011), projected in the back gallery, opens with a quote from Morrissey’s “Sister I’m a Poet” asking, “Is evil something you are, or something you do?” (over a different Morrissey song, “The More You Ignore Me”). In the video, derived from a performance/text by the collective Our Literal Speed, the words “The American Civil Rights Movement took hold in a society moving from radio to television” appear on a solid gray background, and imply a transition from a “social collectivity dependent on imagination” to one where “everything is instantly visible.”

Cokes uses the medium of video not to mimic television’s instant visibility, but as a vehicle for words—for imagination rather than image—drawing from the affects, flows, and processes of music (a non-representational form) to explore video’s non-representational qualities. Selma, like much of Cokes’s work, decouples word from image to ask how our modes of political and civic articulation are guided and shaped by image circulation, which defines the horizon of emancipatory struggles. Cokes proposes that a deconstruction of media is fundamental to liberatory politics, and he offers contemporary art as a space for experimentation as well as critiques of the regime of visibility.