Ull Hohn at Greene Naftali reviewed in Texte zur Kunst by Joel Danilewitz

Greene Naftali

Exhibition

ULL HOHN

No Great Mysteries

Curated by Monika Senz

8th Floor

Greene Naftali is pleased to announce a solo exhibition of work by the late German painter Ull Hohn (1965–95), his first in the U.S. in over ten years. In the brief span of his career, Hohn developed a singular body of work that was stylistically promiscuous but conceptually coherent, engaging the history of painting slant to refine an approach both analytic and personal.

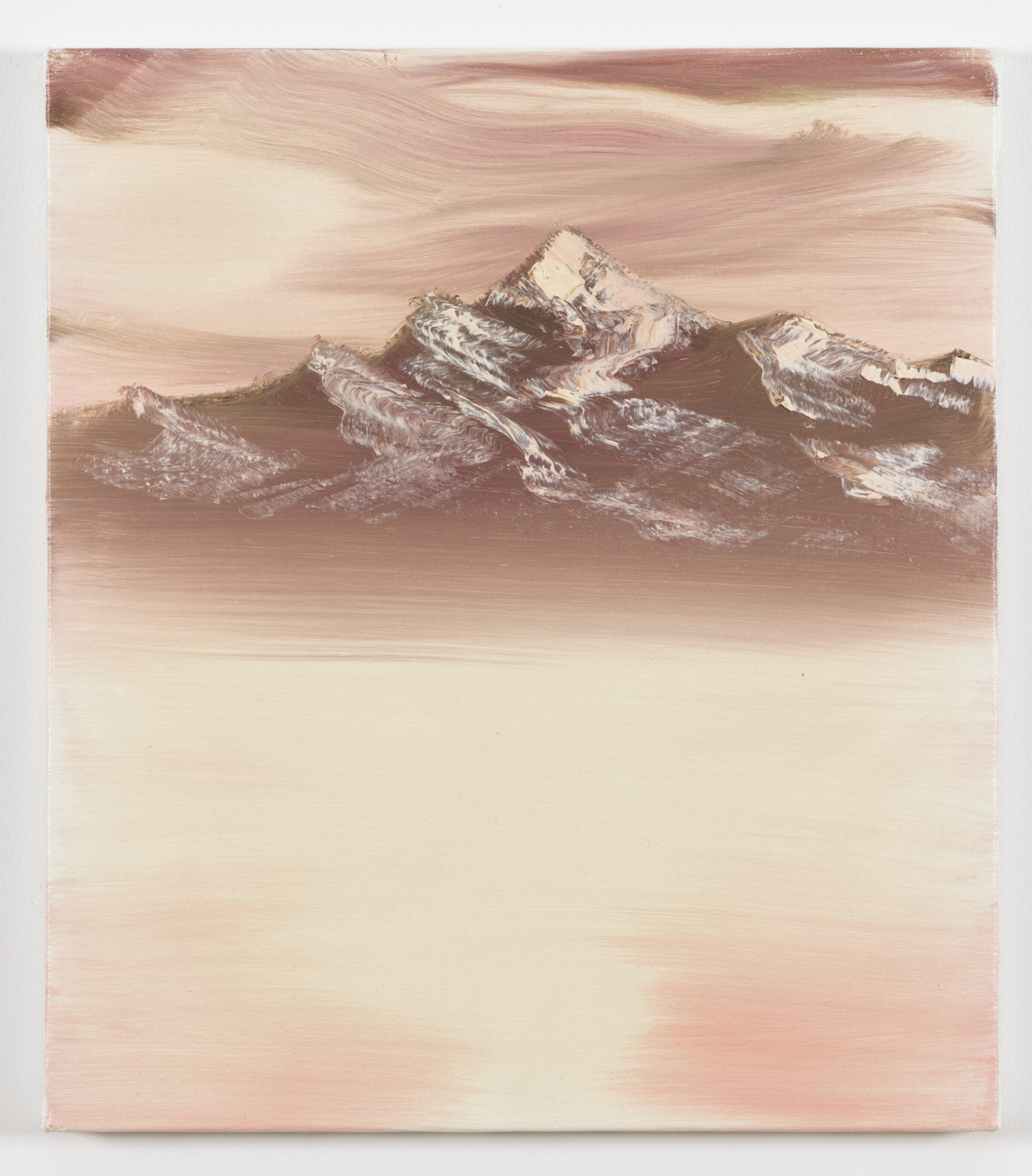

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1993

Oil on canvas

16 x 20 inches (40.6 x 50.8 cm)

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Hohn trained at the Düsseldorf Academy under Gerhard Richter before moving to New York in 1986, where he enrolled in the Whitney Independent Study Program. The ISP’s theory-driven environment recast Hohn’s idea of painting, then considered outmoded and fatally detached from the events of the day. Yet he remained dedicated to the medium and worked to renovate it from within, employing a battery of formal techniques toward a more discursive practice. On view are a number of previously unexhibited works from this formative period, which treat painting from a place of both critical distance and lingering attraction. Marbled swirls of enamel, varnish, and lacquer seem to liquidate the heritage of gestural abstraction, and other small-scale works used plaster to build unusual topographies in high relief. The son of an architect, Hohn used these works on wood as studies to explore more dimensional supports, providing himself with uneven grounds on which to paint anew.

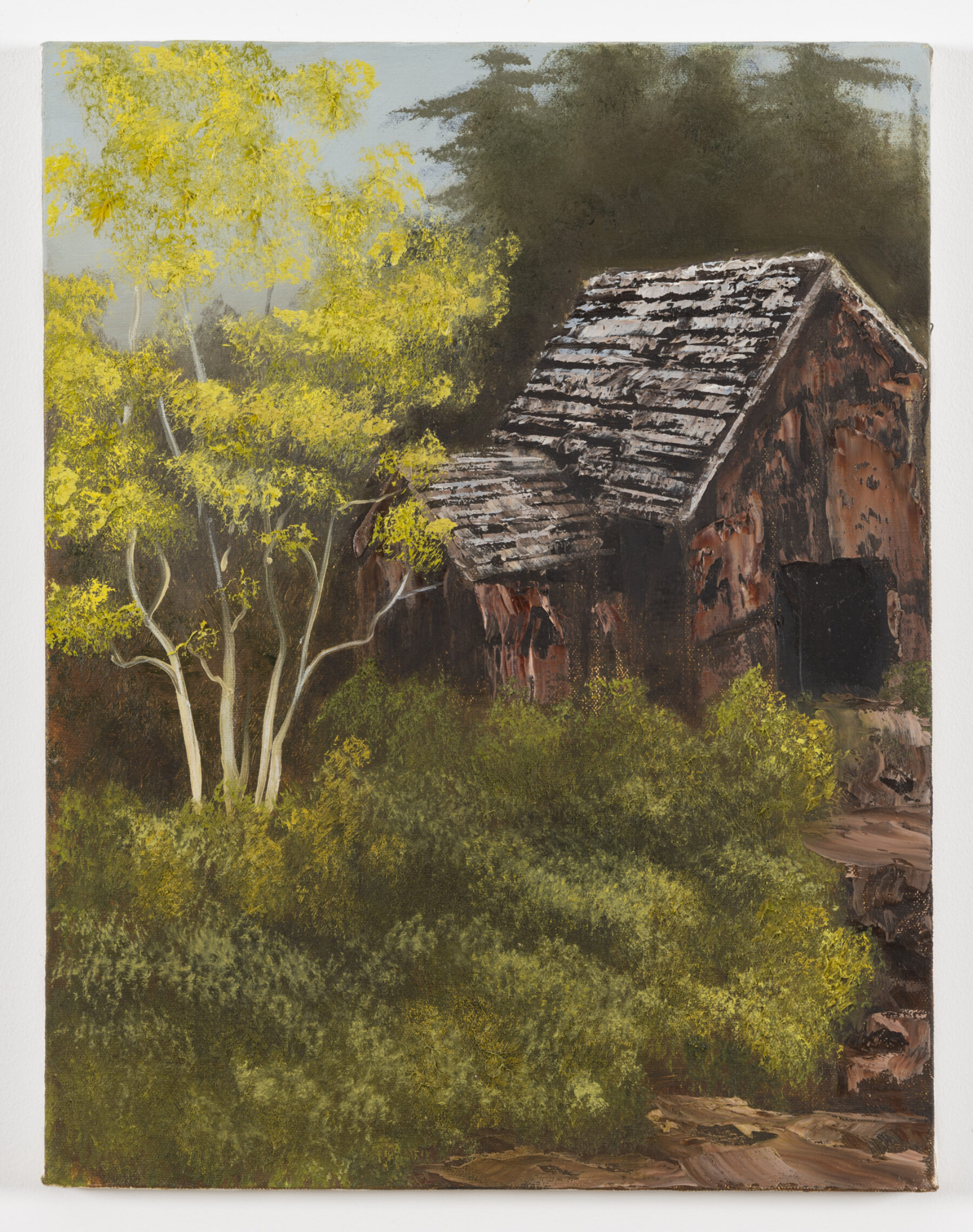

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1992/1993

Oil on canvas

18 x 16 inches (45.7 x 40.6 cm)

The artist’s arrival in New York also coincided with the height of the culture wars, when the gay community was organizing itself against the AIDS crisis and the conservative backlash of the Reagan era. In that politicized climate, allusions to gender and homosexuality began to crop up in his work—as Tom Burr put it, Hohn wanted “the act of painting, and the specifics of his biography as a painter, to fuse.” Swipes of squeegeed color could form tasteful backdrops for less sanitized motifs: stenciled silhouettes of an erect penis that filled the surface of the canvas. Frank acknowledgments of sexual identity, these 1986–87 works also nod to the outsized role of the phallus in the emerging field of gender studies, or to the so-called pattern painting of his contemporaries like Philip Taaffe (whose garnishings were already considered somewhat passé in Hohn’s circle). At the ISP’s culminating exhibition in 1988, Hohn showed a set of brown monochromes—slathered and gleaming—that liken the painted surface to chocolate or feces, melding abjection and libidinal pleasures.

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Even Hohn’s landscapes work to subvert painterly conventions, resembling a fusion of the Hudson River School’s epic pastorals and the middlebrow fare of the Sunday painter. Works from 1992–93 were based on those of public television sensation Bob Ross, whose syndicated program delivered step-by-step, genial guidance to produce anodyne nature scenes. Painting à la Ross let Hohn work in ways that were anathema to the art world, tacitly questioning the hierarchies of skill and class that determine how painting is received. These “Joy of Painting” landscapes demystify the genre, while also retaining a strangeness that effects a kind of kitsch sublime. An (unattributed) quote from Ross served as the epigraph to Hohn’s 1993 solo exhibition at American Fine Arts: “There are no great mysteries to painting. You only need the desire to paint, a few basic techniques and a little practice.”

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1993

Oil on canvas

18 x 14 inches (45.7 x 35.6 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1993

Oil on canvas

18 x 14 inches (45.7 x 35.6 cm)

Following Hohn’s untimely death due to AIDS-related complications in 1995, his work was little-seen for several decades, but has recently experienced a resurgence of critical interest and visibility. Restless but never cynical, Hohn’s work provides a historical bridge to a sensibility that has since become far more prevalent—to view painting as a set of conscious gestures of deferral and evasion yet seek to innovate nonetheless.

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1993

Oil on canvas

18 x 18 inches (45.7 x 45.7 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1988

Oil on plaster and wood

Overall Installation: 20 1/4 x 214 x 3 3/4 inches (51.4 x 543.6 x 9.5 cm)

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1987

Oil and tape on canvas

16 x 18 inches (40.6 x 45.7 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1987

Oil on canvas

16 x 18 inches (40.6 x 45.7 cm)

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1986

Oil on canvas

16 x 18 inches (40.6 x 45.7 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1987

Oil on canvas

16 x 18 inches (40.6 x 45.7 cm)

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1987

Varnish and lacquer on wood

7 1/2 x 11 1/4 x 3 inches (19.1 x 28.6 x 7.6 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1987

Enamel and varnish on wood

10 x 8 x 3 inches (25.4 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1987

Varnish on wood

10 3/4 x 10 3/4 x 1 1/2 inches (27.3 x 27.3 x 3.8 cm)

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1988

Plaster and oil on wood

10 x 8 x 3 inches (25.4 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1988

Plaster and oil on wood

10 x 8 x 3 inches (25.4 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1988

Plaster and oil on wood

10 x 8 x 2 1/2 inches (25.4 x 20.3 x 6.4 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1988

Plaster and oil on wood

10 x 8 x 3 inches (25.4 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm)

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1986

Oil on canvas

12 x 12 inches (30.5 x 30.5 cm)

Installation view, Ull Hohn. No Great Mysteries, Greene Naftali, New York, 2023

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1987

Enamel and varnish on wood

9 1/2 x 9 1/2 x 4 1/2 inches (24.1 x 24.1 x 11.4 cm)

Ull Hohn

Untitled, 1987

Enamel and varnish on wood

14 1/2 x 14 2/3 x 2 2/3 inches (36.7 x 36.5 x 6 cm)